Politicians with weapons in the closet

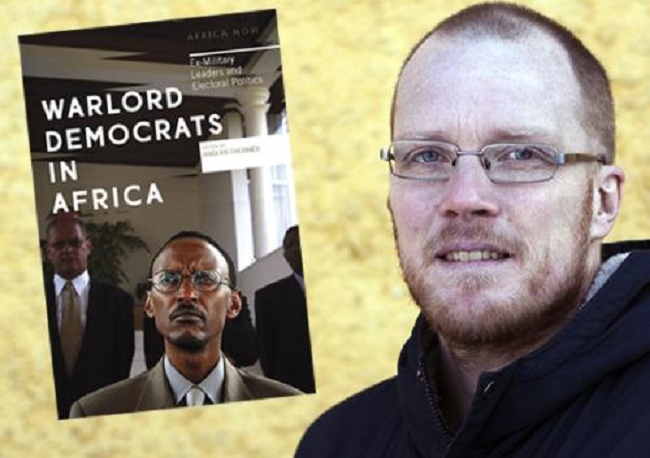

The book’s editor Anders Themner says ‘former soldiers are considered to be strong leaders”

Can we really trust former military leaders who become politicians? It is a common feature of many war-torn African countries and the subject of the book, Warlord Democrats.

A military background is often beneficial for men – they are almost always men – with political ambitions. This is not unique to Africa, but common the world over.

“It signals decisiveness. They are portrayed as men who get things done and are not afraid to deal with sensitive issues. Former soldiers are considered to be strong leaders”, editor of the book and NAI researcher Anders Themnér says.

Iron fist

However, research shows that few really transform completely. One reason is the positive image a military background confers: since leaders actually gain popularity from having such a background, they emphasize it. Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame is one such example. He deliberately highlights his role in defeating those responsible for the genocide in 1994 and securing peace afterwards.

“More and more frequently, I hear people call for strong leaders, also among African scholars. It is worrying that many have more confidence in strong leaders than in democratic systems and institutions. But that’s probably the thing: in war-torn countries, few state functions are working. Then it is reasonable to prefer a leader who rules with an iron fist”, Themnér notes.

Lacking standards

In Western democracies, people are socialized into democratic society. They learn how to behave through functioning institutions and shared values. Even anti-democratic views are allowed, since the idea is that extremists will eventually adapt themselves, and learn to respect how society works. In many African countries this does not happen because of lacking democratic values and institutions.

“Then political issues may turn violent. Not because these leaders are more evil, but because there are no clear values and standards. In that sense, former military leaders are socialized to become autocrats rather than democrats”, Themnér observes.

Calculated conflict

One chapter in the book deals with Mozambican opposition leader Afonso Dhlakama who, 20 years after the end of civil war, took up arms again. According to the chapter’s author Alex Vines, this was in no way sudden or impulsive. On the contrary, it was carefully calculated.

Dhlakama’s party Renamo was formerly a rebel group that fought against the Frelimo government during the 1970s and 1980s. Following the 1992 peace agreement, Renamo became a political party. Many independent observers agree that Renamo actually won the elections in 1999, but that Frelimo stole the victory. Dhlakama gradually became more marginalized as he lost election after election. Eventually, when his own cadres began to question his authority, the situation became desperate. This is when Dhlakama started to threaten a return to violence. His speeches became more extreme until things escalated into a real violent conflict.

“This was probably not Dhlakama’s original intention. But rational calculations of power gave him the option of armed conflict. And this is the risk with warlord democrats – they have the knowledge, the resources and the networks to use violence if all else fails”, Themnér states.

TEXT: Johan Sävström